Hoover Color closes after vivid history

Photos by William Paine/Patriot Publishing

Photos by William Paine/Patriot Publishing

Hoover and Bowman and the mine carts

From left: Burl Bowman and Charles (Chuck) Hoover the 5th stand in front of the mine cars used to take the iron ore from the mines to the color plant. Mules, which were rented from the locals, pulled the carts back up the mountain to the mines.

By WILLIAM PAINE

Patriot Publishing

Ending more than a century of pigment production, the Hoover Color plant in Hiwassee will cease all operations by the end of May.

Although as Charles (Chuck) Hoover the 5th explained, the pigment production facility in Hiwassee wasn’t always owned by the Hoover family. Before Charles Hoover the 3rd acquired the color plant in 1973, the Hoover family was a customer of the color plant.

Beginning with Charles Hoover the 2nd, the Hoover family has been in the pigment business for four generations. Charles Hoover the 5th replaced his father, Charles Hoover the 4th, as Site Manager of the Hoover Color plant in 1983. In 2019, Burl Bowman, who has worked at Hoover for 39 years, took over as Site Manager.

“My father was here for 41 years,” said Bowman. “My grandfather worked here. So, my family has 80 plus years here and I’m not the only one. We’ve got multi-generational families working here.”

So why, after all of these years, is the Hoover Color plant closing?

Part of the reason dates to 2016, when leading global iron oxide pigment manufacturer Cathay Industries acquired the Hoover Color Corporation. Before the takeover, Charles Hoover the 5th had a serious discussion with his children.

“The reason we ended up selling out is I gave my kids until they were 30 to decide if they wanted to go into the family business or not,” Hoover recounted. “They decided not. They had other things they were pursuing and so that’s when we merged the company with Cathay and Cathay eventually restructured or merged themselves into Oxerra.”

“Oxerra had the opportunity to buy out one of our major competitors, who had a facility in Augusta, Georgia,” Hoover continued. “The original plan was to close Georgia and move some of our production to our Asian facilities, but that didn’t work out because Augusta can do what Hiwassee does but Hiwassee can’t do everything that Augusta does. Augusta is a newer facility. So, this winter they made the decision to shut down Hiwassee and move everything to Georgia. Some of the higher end products will be made in Asia.”

As a result, the 18 individuals currently working at Hoover Color plant will no longer be employed when the plant shuts its doors for the last time. In the 1940’s the color plant employed over 100 people, but Hoover Color plant generally employed 50 or less workers in the modern era.

“The county has been great in supporting us,” said Burl Bowman. “We’ve had people on site helping us find jobs and make the transition. Some folks have already gone for interviews at James Hardy and Volvo. Those are usually two big ones. A few folks are at the age where they can retire. They’re just gonna do that. We offered positions in our facility in Georgia but nobody wanted to move and that’s understandable. I’m gonna stay with the company. We’ll see how that goes. I might just travel, too. We also have a place in Los Angeles too, but I’ll take Georgia over California.”

Fluctuations in the market constantly shape which industries thrive and how long they stay viable, as Hoover himself noted.

“The history of this place goes back to the Civil War and the Cloyd Mountain Battle,” said Hoover. “A young Union soldier who ended up over here started seeing lots of iron ore. His family had an iron foundry up in the Philadelphia area. After the war he came back and, Carpetbagger that he was, bought up the whole side of the New River and started the Bedford Iron Works. There was always an overburden of pigment material that was associated with these iron deposits and my family would buy those pigments and process them up in the New York City area. That was Charles Hoover the second. So, there was a period in the late 1800s when this was the iron mining center of the country.”

The iron industry thrived as massive stone furnaces were built to smelt the ore, which was then transported by river barges and eventually by the newly built railroad to be further refined. This all changed by the turn of the 20th Century, when vast iron deposits of higher purity were discovered in Minnesota.

“So, when the iron industry falls apart around 1910, Bedford Iron Works restructured themselves and changed themselves into the American Pigment Corporation and became a pigment company,” said Hoover. “They pivoted and built the Hiwassee color plant and the Pulaski Plant that eventually became Magnox. They made the iron oxide that went on the tape that recorded the magnetic signal. Magnox was our sister plant. A company called Hercules, which ran the arsenal at one time, was looking to diversify and they wanted the Magnox plant.”

“Well, the owners of American Pigment weren’t going to sell them half their business, which was also the most profitable part of their business,” Hoover explained. “So, Hercules bought the whole thing in the early 1960’s and then ended up spinning the Hiawassee facility off to my father in 1973. Before that, we had our own business in New Jersey and he was a customer of Magnox and Hiwassee. So, he would buy raw pigments from these facilities and further process them up in New Jersey”

“Nowadays we go into Home Depot and Lowe’s or Sherwin Williams and they have a zillion paint chips up on the wall and you take that paint chip up and they squirt in the concentrated colors and shake that up,” Hoover continued. “Well, that technology wasn’t developed until the late 70s. Before that, in order to get a specific color, you had to have somebody blend raw materials to make that. So, my great-grandfather came up with things like the brown for UPS trucks, which was a specific color made for identification purposes and that’s what the original business was.”

The pigments produced by the Hoover Color plant are iron based and come in either a yellow, red or brown form. Until 2010, the iron ore processed by the plant was extracted from mines located on the mountain behind the plant. When this process began, the ore was transported down the mountain with wooden carts that traveled on tracks. Mules pulled the carts back up the mountain to fetch another load of ore.

“The color industry is kind of unique,” said Hoover. “People who make white, don’t make black. People who make red, don’t make blue and we’re the people who make what are called the earth colors. We’re here because of a natural yellow deposit. But we also brought in ores from around the world and process them here.”

What actually happens inside the color plant?

“So, there’s a lot of particle size reduction grinding that goes on here,” Hoover responded. “A pigment is a very fine and soluble powder. So, we’re trying to get our particles down to about one micron. A human hair is 100 microns, so that’s 1/100th of a human hair. A lot of what we do here is grinding. We take a rock and we make a pebble. The Pebble we make a pea-sized. From the pea, we made a sand sized piece and we take the sand and make our finale pigment.”

The paint lab at Hoover Color was used to make sure that the pigments produced at Hoover Color met strict color consistency specifications.

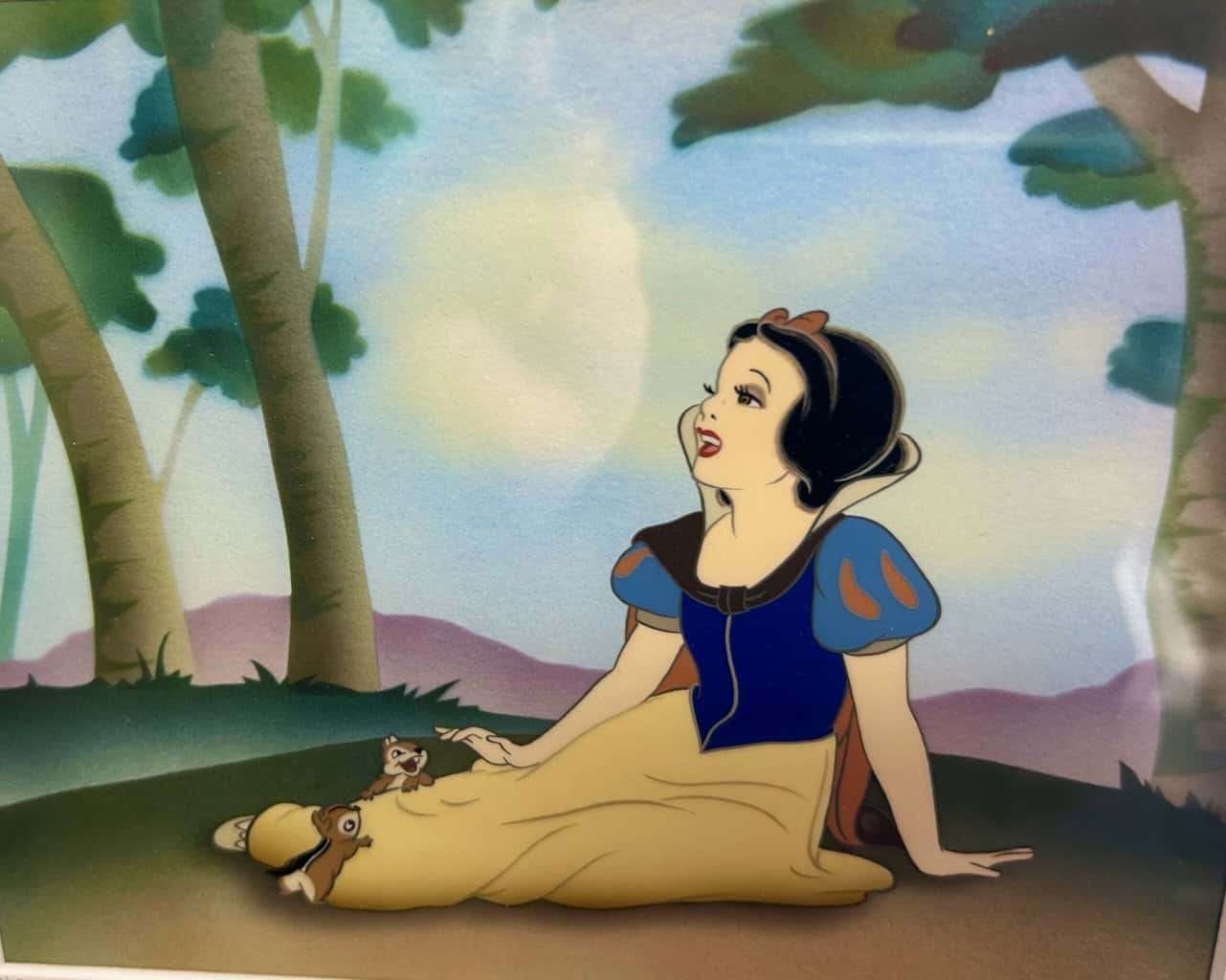

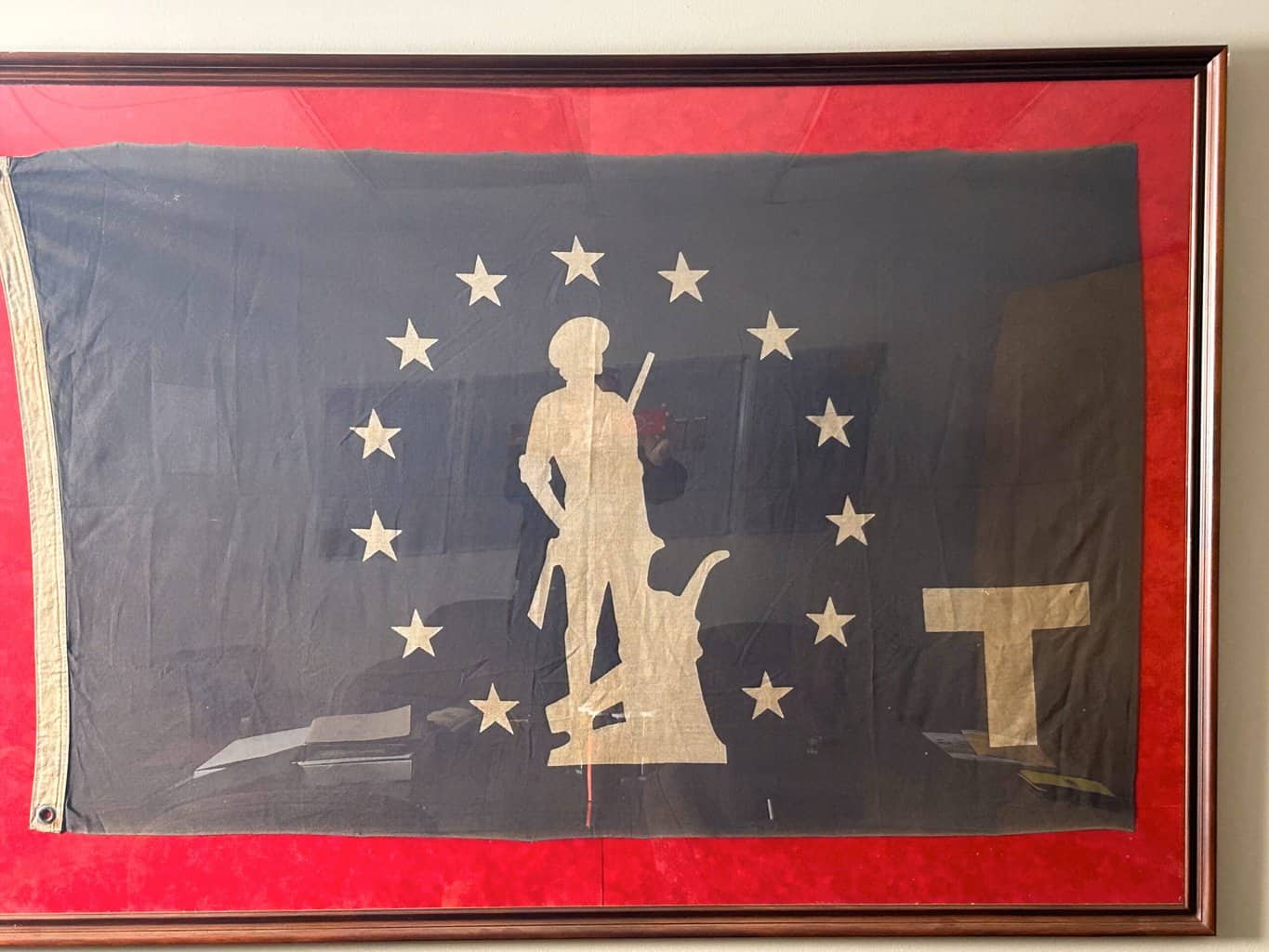

The Hoover Color plant has gone through many changes throughout time. A general store once stood on the site that now serves as Hoover Color’s central office. Inside the office there are several mementos from Hoover Color’s past. A picture taken from Walt Disney’s animated film Snow White hangs on one wall, while a flag emblazoned with a large T is positioned behind the desk.

“That’s one of the original cells from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” said Hoover. “We supplied all the earth colors for that. In World War II, we made the olive greens for camouflage uniforms and so we were given this flag for the Minuteman Award. The T is for “technical excellence”.”

“Every time you turn around you find a piece of history,” Bowman remarked.

For nearly a quarter of a century, from 1990 through 2014, Hoover Color produced all of the pigments for Crayola crayons.

“We would buy the blue and buy the white and through our mixing process make periwinkle blue,” Hoover recounted. “That was a huge commitment. It probably took half of our workforce. At the time, we were making all of the Crayola colors in the world.”

Lately, one of the biggest markets for Hoover Color has been the red, yellow and black pigments produced for interlocking concrete blocks and roofing tiles.

“Most people don’t even think about it,” said Hoover. “You look at something like an electric outlet. Somebody had to make the color in that plastic. We’re way back in the supply chain of just about anything.

“The biggest white pigment is titanium dioxide,” added Bowman. “That’s the base white color for your paint. That titanium dioxide in a different purity form is also found in your toothpaste and it’s in powdered white donuts … We make food grade pigments in our facility in Italy. It’s only made in Europe. We’re expanding that in one of our China facilities. This plant is a small piece of the big picture footprint of our global parent company (Oxerra) headquartered in Singapore. It’s Asia controlled.”

“The industry started with a lot of really small regional people like Hoover Color and over the years, we’ve all been consolidated,” said Hoover, who currently works as a consultant for Oxerra. “Right now, there’s a big German company that is our competitor. We are considered more of the Asian company. We’ve been fighting about Astroturf lately. We’re trying to get our green versus our competitors green in Astroturf business.”

Charles (Chuck) Hoover the 5th grew up with the Hoover Color plant and has spent a significant portion of his life running the facility. It was he that chose to donate 250 acres to the Virginia State Park system for Hoover Mountain Bike area in 2019 at the site of the former Hoover Color mining operation. Does he feel a sense of sadness on the thought of closing this facility forever?

“Yeah, but it’s amazing that it lasted this long,” said Hoover. “You look at the Magnox plant in Pulaski, which was the new facility with state-of-the-art technology. That probably lasted 30 years. But we go back to … the pigments that we make go back to the original cave paintings. So, we have 70,000 years of mankind using these pigments.”

Up until the final day of operation, which was scheduled for Friday May 31, Hoover Color operated two-10 hour shifts for five days a week, so that for 20 hours a day the plant will be running, so as to build up inventory before the doors close for good.

June 4, 2024 @ 10:25 am

What a fascinating story! Maybe those old mine carts can be donated to the transportation museum in town if the family doesn’t choose to hold on to them.

June 5, 2024 @ 8:08 am

Awesome info most people in SW VA would like to know this history for sure. Crayola colors. Green for WWll uniforms what a great accomplishment to be proud of. Sad to see it go . I had 2 uncles retire from the Pulaski plant yrs ago, I worked for a construction company there in the early 80s . Amazing the history around us and we don’t even know it. Thks for the article. 👏👏

June 5, 2024 @ 1:44 pm

Did any of the pigments come from the Allison family back in the 1940s through the 1950 s from their land ?

June 6, 2024 @ 9:53 am

My step grandfather David Hoover was also a part of the Hoover plant at one time with his brother chuck. He has since passed away in July of 2020.

June 7, 2024 @ 12:15 am

Totally awesome piece of history. Very very interesting. All the stages, the colors, the family business aspect and history of holding on to something that you believe in and made a living for generations. 👍🏼👍🏼👍🏼👍🏼😄